Dear Characters: A Love Letter to the Ones Who Stayed

Dear Characters,

You’ve been on my mind lately.

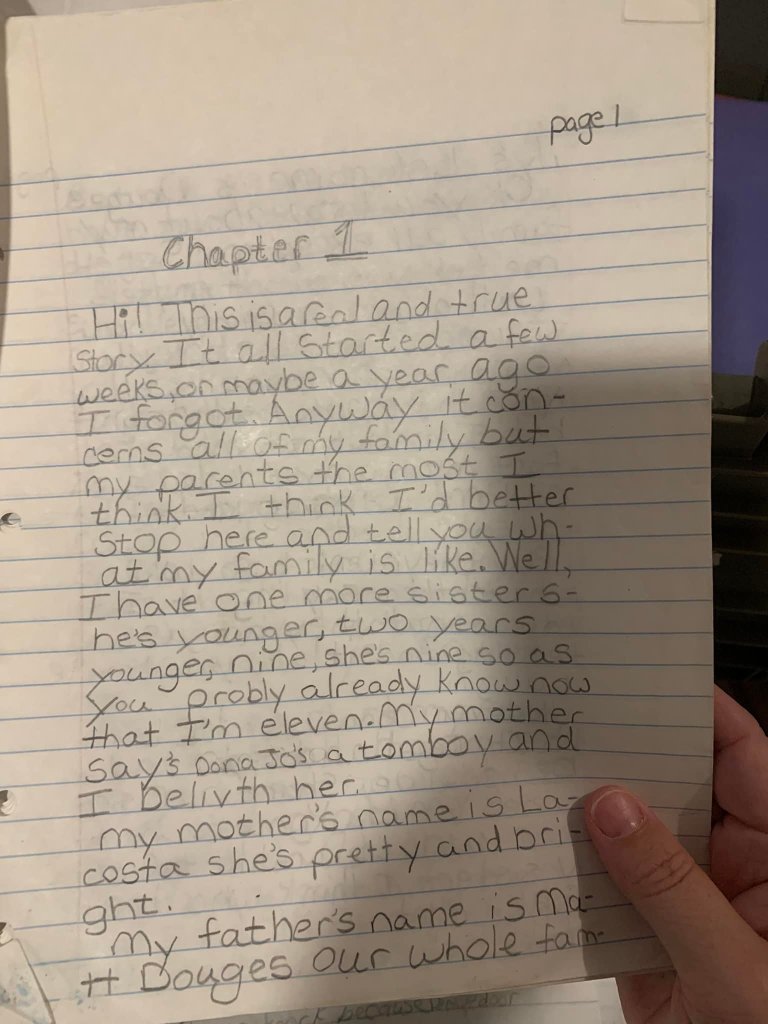

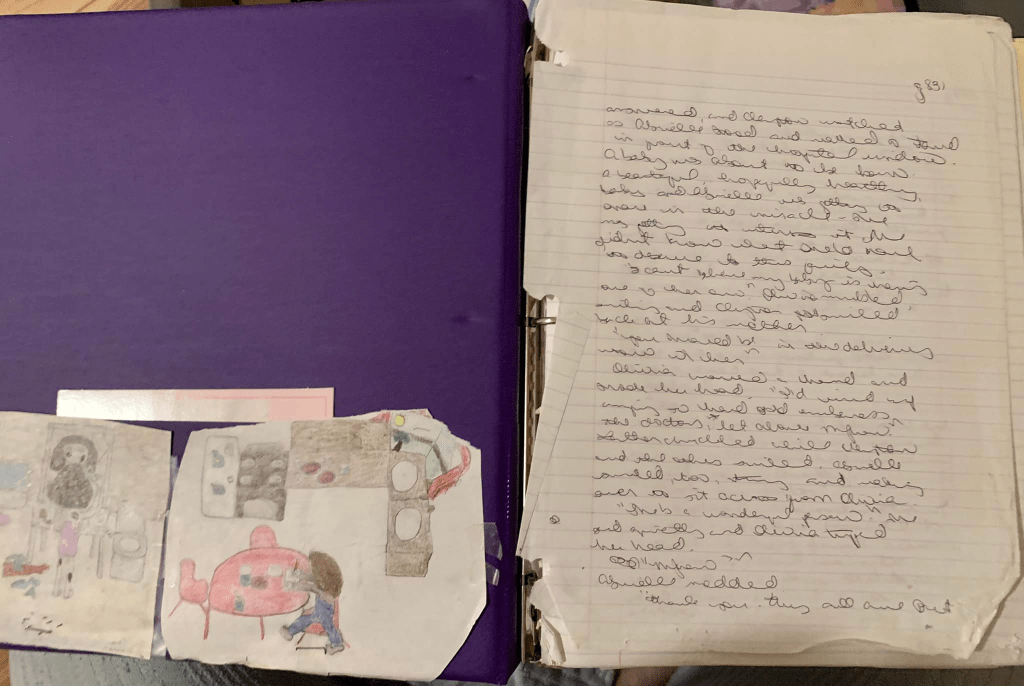

I dreamed about two of you last night and, when I awoke, my first thought was: you stayed. Which, in my life, is an unusual thing: I can’t really think of anyone–character or human–who has chosen to stay. The baggage, you know; it tends to do a nice job of encouraging humans to move along. And you…. well, you characters have never stayed. Instead, you haunt me, day in and day out, until I write the final word of your stories and then… poof, you’re gone. The lot of you have done that since I wrote the first story at six-years-old. Sometimes, I’ve wondered why: do you visit other writers after you leave me and, if so, with what stories? do you leave just to make room for the new characters so the playground that is my imagination doesn’t get too overwhelmed or crowded? From Mickey, who ran the Friends Series written in elementary school to Ainela, the primary heroine of Whisperroot: A Hushwood Tale, there’s been well over a couple hundred of you. Be kind of like backstage at American Idol: crowded, loud, and just this shy of chaotic. For the most part, I don’t question it: you are my friends for as long as your story lasts, and I… well, I am just the vessel happy to have known you. Someone said once that, when I talk about you all, it sounds like I’m talking to ghosts I love. There have been one or two of you whose stories I deliberately postponed writing the final chapter of because I didn’t want you to leave, and I knew you would as soon as I wrote the final word.

Except for a few of you. Every rule has its rebel. And a very few of you creative souls simply never left. Instead, you’ve just faded into the shadows, allowing me to hear and focus on the newer characters’ tales. But you’re there. Yours are the stories I re-read when I’m aching for a friend or a burst of tenderness. Sometimes, I sense you when I’m writing and immediately feel my heart squeeze as it misses you. For a couple of you, I’ve wondered, every once in awhile, does she have another story? would he let me bring him back? There’s a selfish part of me who isn’t really as interested in the story so much as visiting for a little while with an old friend.

And so–this is for you.

A letter to say I see you. I remember you. And I love you for choosing to stay.

The below was the initial idea for Mountains of Hope, the second book I wrote about The Holocaust. I finished it when I was sixteen; my AP English teacher, Dr. Estes, read it. And it would become the first book published. It held two characters who stayed with me for years: Alyx and Tony.

Alyx, you were just a young girl who discovered a crashed plane with American soldiers. You hid them, gave aid to them, and protected them. When you were betrayed, and sent to Auschwitz, the memories of the soldiers carried you through. After the war, when you stumbled out of the camp, you saw a Jeep with American soldiers and recognized Tony. You were ashamed because you did not hair, but you did have lice, and you felt like the dirty Jew the Nazis told you that you were.

You’ve stayed with me.

By far, you’re the quietest. But I can’t talk about the stories without talking about yours. Because you were one of the first characters who held something I held: shame. I’m not sure if, at the time, I knew the word for the emotion – but I knew I recognized pieces of me in you. There was shame and there was loneliness and these things–they were shaping me while I wrote your story. It’s been years since I’ve re-read Mountains of Hope and I’m sure I don’t really want to but… when I thought of the impact I wanted my writing to have on others, I thought of this excerpt, where you watch a brave girl defy a Nazi soldier and there was a part of you that just wanted her to obey. That crushed my heart because I thought obedience meant safety, too. And, yet, both of us would choose to become rebels when given proper incentive. For you, that was protecting the only people who had ever been kind to you. For me, it was protecting my unborn baby girl. I have always been proud that Mountains of Hope was the first book published and, even though I’m sure it could benefit from a good editor and a re-write, I still carry it close to me.

I’m not sure why you’ve hung around for the last 29 or so years. I’m rather surprised you haven’t had another story to share with another, worthier writer in the last two decades. I’m guessing it’s because you were born after the research that started with The Holocaust: A History of the European Jews by Gilbert. You survived Auschwitz. You found the soldiers. You went on to marry and have a son. And the loneliness that first drew me to you – after the war, you filled it with friends. You’re a reminder, then, of what the Holocaust taught me: believe in hope, fight for hope, even when you’re standing in front of a sadistic Nazi bent on destroying you.

In 2023, I visited Poland and went to Auschwitz. It was heavy and it was sad and I cried. But do you know who went with me? My daughter Breathe. Hope is real – and, just as it did for you, it has shown up in my life, too.

I hope you stay for another 30 years.

I don’t remember when I wrote Dreams of the Heart. I know it was the first novel written that breached 1,500 handwritten pages, and I think that happened at Ezell, which would have meant 9th grade. Who knows? The story follows Landon Montgomery. You are a true-blue cowboy with a heart the size of your Texas ranch. Your passion was giving a safe haven to children with emotional and physical special needs; your secret weapon? Horses–and a dose of authenticity that I haven’t quite been able to match in any character since.

Truth is–I’ve always been in love with you, Landon. You epitomized what I needed the most: someone who would fight for me, someone who would show me compassion while also challenging me to believe in myself. You weren’t afraid of fighting, but you only fought for the abused and hurting kids under your care. Beneath the rough exterior was a little boy who had been hurt and who had grown into a man determined to break the cycle. Other than Ash and Clayton, you are the only character to have ever made it into another story when you made a comeback in Sing Me Home. For years (I’m talking decades, okay?), I tried to re-create you with every male character I ever had to no avail.

You’ve not been as quiet as Alyx over the years–you are the reason I wrote this, an imagined day with three of my most beloved characters. It was one of the most fun pieces I’ve ever written because imagining you putting up with Aria was pure gold. I’ve sometimes wondered why you’ve stayed. You didn’t go poof at the end of your story, which has remained untyped and unpublished, and I’ve often questioned why.

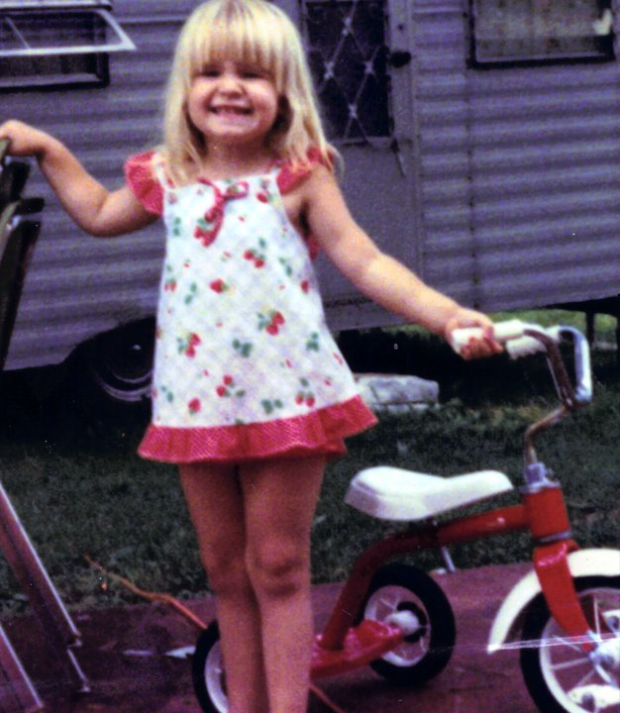

I think you stay because of a line in the book that I’ve never forgotten where you said, “Any cowboy worth his salt never forgets the little man inside.” Just a few short years after writing your story, the little girl would show up. I’d mistake her for a character at first, until I realized she wasn’t there to tell me a story. She was there because she needed protection. You make her feel safe – and I’m pretty sure that’s why you’re still here. You are what she needed then, and you give her the stability, the strength, and the fight to make her feel safe. Writing you was my mind’s way of giving that little girl who and what she needed even when she didn’t have the words to say so. Frankly, Landon, I (and the little girl below) hope you never leave.

Some 26 years ago, when I was somewhere around the age of 19 or 20, I wrote a book whose hero was named Clayton Cunningham. This was an important one for me. I was still years away from disclosing the sexual abuse I went through to anyone…. but it was starting to seep out through writing. This story follows Abrielle Britain who is kidnapped at age 3 and sold to a couple who, basically, sell her out from a very young age for sex. It’s one of the first books I didn’t shy away from abuse scenes. I let her ache the way I did. And I showed what it was like to feel repeatedly violated and that it takes more from you than just something physical.

Clayton, I swear, there’s a piece of me that straight up has been in love with you since you smiled at Abrielle and wryly said, “I’m gonna have to stop telling people my last name so they won’t call me Mr. Cunningham.” And, when Abrielle was spiraling inside, worried that you were going to demand or expect something sexual from her in exchange for lunch, she said, “I can’t pay you back.” You replied, “I invited you…. so—” She interrupted, clarifying, “In any way,” and you snapped your eyes to her and said, “What?” You were genuinely confused. And my heart simultaneously hurt and soared.

Here’s the thing.

I spent years not liking Abrielle. Too weak, I said. I couldn’t tell someone about the book without apologizing for her. I was young when I wrote it, I’d say, as a way of explaining away how static she was. I put as much distance between me and Abrielle Britain as I could. The more years that passed, the more I’d start making excuses for you, too. He’s not perfect; he didn’t handle it like he should have. But he loved her. As I write that, my eyes blur with tears.

You want to know the truth? The truth is–Abrielle wasn’t static or weak. Abrielle was traumatized and suffering from some serious post-traumatic stress disorder. She was submissive because not being submissive meant physical beatings so dramatic she likely feared for her life. She couldn’t be a Taya or an Evariste or any female character I might try to argue was stronger or better written. When I wrote that book, my dad had only been arrested 3 years earlier, and I had not told a single soul about the abuse yet. I still communicated with my dad through letters and phone calls. I was not free. I was still scared. Trust was still hard. Her way out? Art. My way out? Writing. Notice any similarities? I didn’t like her because she was way, way too close to who I was – and I pretty much hated who I was. I had an express, conscious goal with this book: I wanted people to understand that there are types of pain that you never forget. While you can heal from sexual abuse, you can’t get back everything it steals from you. To make that abundantly clear, it needed to be crystal clear to anyone who might ever read it that Abrielle was my pain personified. She couldn’t fight back because I didn’t know how.

And you—you came from a beautiful, Norman Rockwell, safe family. You had friends. You had a stable job. You’d been protected your entire life. And you could have had anyone. Overlooking someone like Abrielle would have been superbly easy for someone like you – she wasn’t in your league at all.

But you didn’t overlook her.

Pete, your father, showed her what it might have felt like to have a dad who loved her. You valued her art enough to put it in your professional art gallery. You introduced her to your friends. And, here is the kicker, here’s where it starts to get really personal for me: when you touched her, she did not feel pain. You showed her what physical pleasure might feel like — and taught her that it was okay to not be ashamed of touch, that you thought her worthy of pleasure. Let me tell you straight: when you climbed into her deathbed at the very end of the book and promised her that angels don’t hurt other angels… Clayton… I was a wreck.

I once read this ridiculous book where the woman read a romance book and went to sleep. When she woke up, the hero of the book she’d read was alive, in real, in her house. If you’re here because you’re planning on doing that, any day would work fine for me. But I know that’s not why you’ve stayed. You’ve stayed because you, and your entire family, remind me to believe in something I can forget: good men are real. Yours is still one of the only books I read at least once or twice a year because there were so many pieces of me in Abrielle that you taught me to believe that someone like me might be able to find a happily ever after, that true love might be real even for someone as broken as me.

You don’t stay because you were so well written (I mean, but weren’t you?). You don’t stay because I straight up adore you. No. You stay because you know I need you. Landon gives the little girl who hides within me safety and protection, but you give the adult Tiffini room to dream without making her feel guilty or ashamed for it. There’s a part of me that is afraid that I can’t find true love because an act is an act is an act – and if it broke a little girl, how can I tell her it’s something different just because I’m older? When Abrielle told you the same thing, you smiled, nodded. Then you kissed her and challenged her to tell you if it felt anything like what she expected. You swore that if she let herself fall with you, you’d catch her. And I believed you.

You made a comeback in The Storyteller and that was really hard because Abrielle wasn’t there and I could still feel the emotion in you over that. She was my wife. Also, my very best friend. Critics would say Abrielle didn’t give you anything in return. You would say, Love isn’t a business transaction. I’m so thankful for what you remind me of year in and year out, for the last 26 years.

Ash, I’ve been staring at this white screen for twenty minutes with tears randomly stinging my eyes. I feel you, moving to the forefront of my thoughts, and there’s just so much to say to you and, since I don’t know really how to start, I’m going to trust you for what to say and how. Again.

I vividly and distinctly remember staring up at ceilings and pretending the plaster was mountains. When I was really young, characters would play amongst them. As I grew older, sometimes the plaster morphed into a gravel road characters traversed. Air vents became caves, or sewage drains my adventurous characters explored. If my dad made me roll over or change positions so that I couldn’t see the ceiling, you’d move down the walls until I could see you. I vividly and heartbreakingly remember panic swelling my chest until I could find you. But you aren’t just one character. You are every, single one of them.

And, when I saw you, I found air. When I saw you, I discovered I had a voice. When I saw you, I could imagine what having a friend might be like. When I saw you, I dreamed. When I saw you, the battlefield lined with explosives that was my mind transformed into a sanctuary where what I thought and felt mattered. I wrote on napkins. I wrote on my hands. I wrote so often my fingers were calloused and permanently stained with blue ink. I fell asleep writing because it was only when writing that I felt safe.

In 2009, there you were. Suddenly, you had a name. But I didn’t know the purpose of the book. All I knew was that there was this character in my head named Ash. When I realized that Anna was going to say all the things that I’d hidden, I panicked. I never could have gotten through it. Except, after every memory, after every scene that was, essentially, me writing out my flashbacks, you were there, telling her a story, encouraging her to write it down. You chased clouds in the park with her and made her laugh when she felt like crying. When I wrote the chapter in which she falls asleep writing down the story you told her, I bawled.

You stood guard and, when the pain became dangerous, when it threatened to overwhelm me, you’d shepherd in a new name, a new character to traverse Plaster Mountain. When I felt hopeless, you whispered, Yeah… but look at this, and bought me a story like Triumph or Strength of a Woman. When I felt worthless, you whispered, I know, but watch this and gave me characters like Clayton or Larissa from Dreams of a Dancer. You’ve always had the perfect character with the perfect story to help me speak. And, when the stories became too much, when the stories meant I needed to confront things I didn’t think I could, you’d whisper, Okay, okay, it’s just a scene. That’s all. Just write this one scene. You don’t have to say anything. Just tell me what you see. Like with Remember the Nightingale and how I didn’t think I wanted to write Gaeton or talk about forgiveness, but you made sure that, when he found Evariste naked and bloodied, Gaeton covered her before moving her body. Such a simple thing. And yet it broke the dam inside my heart open because of how much care it showed her. Tell me who did this to you and, if you need me to, I promise I’ll go.

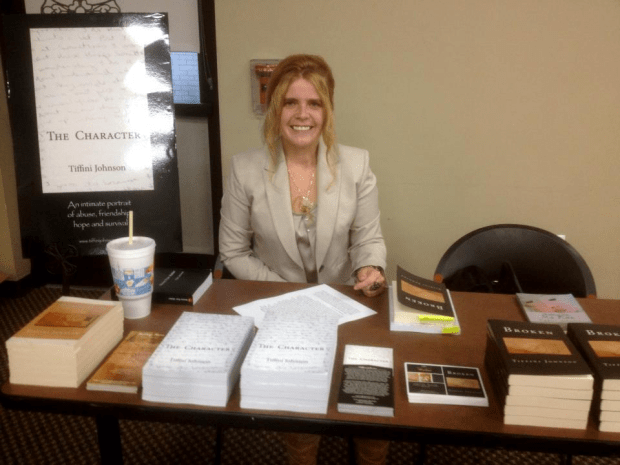

When, at the end of your book, The Character, you came to see Anna… it had been years since she’d needed you. She was published author now and you’d come to the bookstore to stand in line to have her sign a book she’d only written because you’d given her the words. When, finally, you stood in front of her, you said I loved that girl. And I came undone.

You’re my safety net, yes, but you’re more than that. One of the most important things rape took from me was my voice. But, with every character, with every story I’ve written since I was six-years-old, you’ve given it back. You’ve taught me how to take what destroyed pieces of me and rearrange those broken bits into a collage you call worthy. Others see a leader, a teacher, a coach, a writer, a mother, a professional. You see the little girl afraid of taking up space, the girl who craves permission to exist, and you’re still whispering, Let me show you who you are. Be unapologetically you. It’s enough.

Anna’s book, The Character, gave you a name: Ash. You played games with her. You showed her that what she wanted mattered. At the moment of rape, you were there, interrupting the gunshots going off in my mind to tell me about the time you caught a falling star or heard a whistling elephant. Every time I write a book that includes a true-to-life scene of abuse, or a fear born from shame, you show me a way to reconstruct it into something beautiful–whether that be the Storynlight Circle, a shift on the RAINN hotline listening to another survivor in crisis, or writing a book that dares me to confront the thing holding me back. You remind me that tomorrow is a promise, not a threat.

And you are in every character, in every story. One of God’s greatest gifts was the ability to take my holocaust and redefine it until it was the thing that showed me His grace and His hope. In short: you. You’ve been a part of me for as long as I can remember. Others might call it something different: dissociation, for example, but I don’t subscribe to that. You are Ash. The word “ash” comes from the Old English aesc which refers to the ash tree and the remains of fire. A tree is alive. Furthermore, the term aesc can be traced back to the Proto Indo root *as which means glow. So, from the powdery remains of fire (or death, depending on how deep you want to take this) rises something that not only lives but glows. My life has been brighter, and safer, because of you.

I hope you never leave.

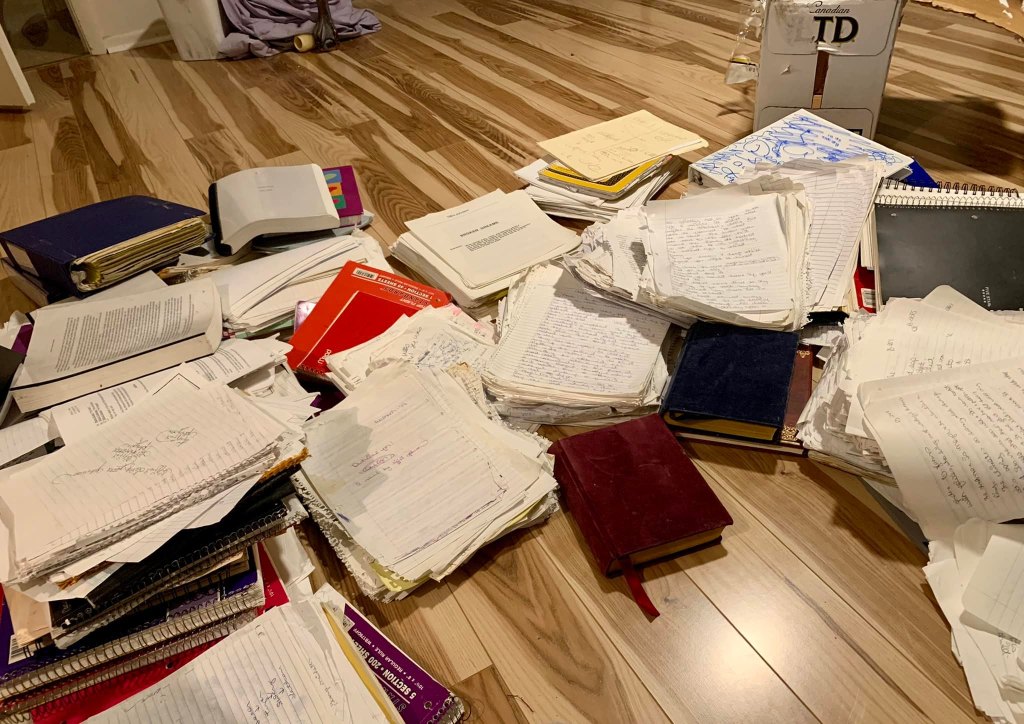

So, then… those of you who have lingered represent reflection, protection, love, and healing. The characters who have come, shared, and gone are not forgotten. Their stories, whether they be published or in a tote amongst thousands of handwritten pieces of paper, helped scrape out and carve my path. For me, the tragedies of our lives are the most painful in the immediate aftermath of the crisis when we’re in shock and actively bleeding from our hearts. Each of you, characters born of that blood and shock and fear, have gathered and shaped the embers into stories that do more than entertain: they share who I am at my core with others. And in sharing the vulnerable, fragileness, I open myself up to rejection, ridicule, shame… and truth, creativity, strength, and hope. Writing is more than “what I do” or a hobby. It is my native language of intimacy. It is how I let others know who I am by saying what’s real. Each story is a piece of my inner landscape mapped out.

How lucky am I.

[…] Dear Characters: A Love Letter to the Ones Who Stayed […]

[…] Dear Characters: A Love Letter to the Ones Who Stayed […]