Apricot

Sometimes authors write to entertain. Sometimes they write to teach. Sometimes they write because the characters are driving them insane. And, sometimes, they write to heal. This is a difficult chapter for me, and one I nearly decided not to share. Making myself vulnerable, though, is important because I want to show my girls that it’s through vulnerability that we share who we really are with others…and find strength where once there was none.

This excerpt is from Sage’s perspective from the forthcoming novel River’s Rowan. Other excerpts can be found under its page. This tells the story of a group of teenagers — four girls, one boy — whose lives are impacted by a broken heart, a shocking betrayal, a tragedy and then one psychotic father bent on revenge. It is long and raw and unedited. It does contain passages that could be triggering to abuse survivors.

….

I didn’t mean to cry.

I don’t know why I did.

I knew better; I knew it didn’t make a difference. It upset him. I should have been able to keep quiet. “Please stop; please, it’s hurting me.” I shouldn’t have asked him to stop; it’s not easy for men to stop. They shouldn’t have to. Especially fathers. Even though he’s not my other daddy, my real one, he’s the one that’s always treated me the best. He wants me to call him Daddy. Have you ever gone hungry here? No. Have you ever had to sleep outside or get clean in the pond? No. Did you ever get nice things before, did anyone ever give you gifts? No. Even when I’m in this room–this room is better than the shack he rescued me from.

I remember that wounded house. I’d be crazy to want to leave this for there.

It sat at the bottom of a gulley, the old house. Overgrown grass sprouted everywhere. At least two snakes lived under the porch: I’d see them every now and then slithering into or out of the hedges. I wasn’t scared of the snakes, though: they weren’t the poisonous life there. Here, there are acres and acres of manicured lawn: the only things overgown are the huge trees near the garden. Those trees sprout delicious apples and peaches. I’ve never seen a snake here: the only animals are the horses that live in the red and white barn.

It wasn’t just the outside of the shack that made it so hard. Walking to the well, hauling water, going outside at night to go pee – I didn’t know anything else, so I could have kept doing that. The Touch made it bad, but I might could have stayed even with that. It was the beatings: he said nobody would give two cents if I disappeared one day, and that, if I didn’t act right, he’d make sure I did. We were miles from anything; nobody ever drove the old road at the top of the hill, nobody knew we were alive at all. Me living or disappearing made no difference to the slow, broken world of the gulley. People are always coming and going from the big house. There’s the gardeners, the cook, the house manager, the pool people. Everyone is very polite: people notice me, ask how I am, say hello; I haven’t been thrown against a single wall.

The shack wore a slanted roof made of tin. I hated the rain cause it made a ping ping ping sound on the roof. It sounded like someone hammering up there, trying to break in, during a thunderstorm. Two of the planks that made up the porch rotted: I’d never step on those two planks because I thought they’d break and I’d go falling under the porch into the darkness, where the snakes lived. He said the dirt was soft under there, good for burying bones. I dreamed in nightmares, of those rotten planks breaking, me falling into the wet, soft dirt, turning my head to see a whole army of skeletons laughing at me. The sunlight couldn’t get through most of the house cause it didn’t have many windows. Dirt and grime smeared the glass of the few narrow ones it did have. A layer of dirt covered the wooden floors inside, too: the soles of my feet stained black from walking on the dirty floor. The shack didn’t have many things: water, electricity, furniture. Only a wood-burning stove for the winter, and a couple chairs he built by hand. The sheets weren’t the only stained part of the bed: the mattress itself wore faded, irregular spots of dried blood and other fluids. There’s nothing the same about the big house. It has black tiles on the roof that I’ve been told are solar panels, three chimneys for the different fireplaces, and floor to ceiling windows that are spotless. It’s hard to find a place in the big house where shadows fall because light is everywhere. The wraparound porch is sturdy and overlooks a huge driveway that has a fountain in the center of it; the room I sleep in has its own balcony that overlooks the pool. The bed itself is spotless as its sheets are washed every Friday and, when I peeked under them to look at the mattress, it, too, looked new. The stains on this bed are invisible.

The Radical Redress, this room, is different altogether. It’s not like the big house or tiny like the shack. He calls it a cabin. Like the shack, it doesn’t like sunlight. It doesn’t have any windows at all. It doesn’t have a bathroom, either: there’s a pot I use and he empties it for me every other day or so. The big house has televisions: I’d never seen one of those before, but they are fun to watch sometimes. The smells of the big house are what I love the most: bread baking in the mornings, warm cookies in the afternoons, and the air itself. Nan sprays the air with a special perfume. I didn’t know there was perfume for the air, but it makes the whole house smell like honeysuckles. The shack smelled of dust and leather and wood. The Radical Redress mostly doesn’t smell at all, unless the pot doesn’t get emptied fast enough. Sometimes it smells of urine. The only thing about all three places that’s the same is the bed. The mattress is stained here too.

“Take that dress off. I want to see what’s mine.” I know he’s angry when he says it. He’s dimmed the lights in my room, and two candles burn on the dresser. He’s angry because I asked to take the ankle bracelet off. It’s rubbed patches of my skin an angry red color, and its weight is uncomfortable. My back burns from the sting of the beating that came after I asked. “I’ve spent hundreds of dollars on you, thousands if you count making you your own house at The Radical Redress. You’ve got clothes,” the belt cracks against my back, licking over my sides, making me wince. “You’re fed every day,” another slap, this one against the backsides of my knees. I fall to the carpet. My breathing turns shallow and I squeeze my eyes shut, shaking my head, trying to shake out the memories. I reach for Apricot, laying on the bed, but the belt smacks across my hands, making me jerk them close to my chest. “Gifts are only for good girls. Girls that I can trust,” he spits the word at me, and this time, it’s not the belt but his fist that hits me across the face. Beatings at the shack were worse. Beatings at the shack were worse. I was thrown against walls; I was tied up. Beatings at the shack were worse. I earned this. I deserved this beating because I wasn’t grateful. “When are you going to learn to be grateful? I rescued you from hell, and you give nothing back to me. All I want is to make sure you are safe, to know where you are, what’s so wrong with that?” I never know, in the moments when he’s the angriest, if he wants me to answer his questions or not. Even if he does want me to, I can’t. Thunder roars inside my head, making it hard to hear or understand anything he says. Instead, I kept my eyes on Apricot.

I love her dress: white at the top with a pale pink skirt covered in white polka dots. The pink heart on the top is my favorite. It’s her way of saying I love you, Sage. I’ve never heard those words, but I pretend she says it. When I hear her voice, it’s soft and sounds like music. He wouldn’t let me hold her; he never does when I’m being punished. He says, I want you to feel this. I want you to hurt the same way you made me hurt. I can see her, though. Her deep brown eyes match her hair that looks like chocolate. The first time I took a real bath–that was in the big house– it made me feel as clean as Apricot. She doesn’t have stains on her feet or her clothes. She’s beautiful. “Take that dress off, and I’m not going to say it again.” My legs and arms still throb from the beating as I stand in front of him. My fingers feel like gloves and fumble with the buttons, so it takes me a few minutes to slide the dress off. It falls into a puddle on the floor; my head is bowed so I see the blue fabric fold around my ankles. He doesn’t speak and I start to feel my arms tremble; I fold them across my chest.

I didn’t mean to cry.

I knew it would only make him angrier than he was.

I tried not to. I don’t know why I did. I should be used to it. My other daddy did the same thing and I didn’t always cry. Even when he was violent, even when he hurt me, I didn’t always cry. But standing in the room with nothing covering me, welts forming on my broken skin, and feeling his eyes watching me was awful. My eyes welled with tears, and I bit my bottom lip to keep it from trembling. “It’s very selfish of you to do nothing but take. You take the food I work for, you take the gifts I spend money on for you, you wear the clothes I buy you. All you do is take when I’ve given you everything. No one’s ever going to want this,” the belt lashes the front of my legs. I hear sounds, the belt dropping to the floor, and look up in time to see him pulling at the buttons on his jeans. I drop my eyes to the floor and the shaking becomes uncontrollable. “It’s time you started giving something to me. Get over here and show me how sorry you are.” Only I can’t move: my legs seem frozen. His voice turns into a really soft warning. “I will not say it again. If I have to, I will take you back to the hell you came from and I will make sure nobody ever finds you again.” Each word feels like a strap against my bare skin, pushing me forward.

My stomach feels awful.

I curl my legs up, holding Apricot, and tuck my face into my stomach, my eyes squeeze, the sounds of my crying shrieking in my head. “Apricot, tell me a story,” I whisper. “Tell me a story.” I open my eyes and stare into the face of the doll. Running my finger over her painted on smile, I can’t remember the last time I smiled.

“I do,” Apricot says. “I remember.”

“Those are apricots,” Nan says, watching me pick a small, fuzzy round fruit from the bowl. “They’re pretty,” I say. “Try one,” Nan encourages. “They’re sweet.” I bite into it and my eyes widen. The tangy sweetness bursts in my mouth. As I eat mine, Nan takes another and holds it up in front of the doll I found on the bed. “Hmm,” Nan says, “She likes it too!” She pretends the doll grabs it from her and she drops the fruit in the doll’s lap. Nan winks, “She’s almost as sweet as those apricots, that doll.” I smiled, staring at the doll’s face. “That’s her name,” I say. “Apricot.”

His hands are against the back of my head, pushing me tighter to him, until I can’t breathe. Gagging, I put my hands on him and push, trying to move back just a little, but he won’t let go, his fingers tangling in my hair. I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe. He pulls my head back and my mouth is free just in time. I cough, gagging, my eyes watering, but I don’t have time to think before he pulls me hard from the floor to the mattress. Soon, tears well in my eyes again, and this time, they spill over. He’s not violent. He’s not violent. He’s not violent. I’m okay, I’m okay. I tell myself that again and again. He’s not violent, but it still hurts. There’s something very wrong with me because it shouldn’t hurt, he’s not beating me or hitting me, but it hurts anyway. He says I make him sick, that he’s seen dogs that look better. The tears start coming more and I cough, trying to get a deep breath. That’s when he gets really angry. It changes. Suddenly, he slaps my face, hard, tells me to shut up.

I squeeze Apricot, tell her it’s okay, he’s not here right now, no one is here right now.

When he was done, he told me to get dressed. Since you’re wanting to leave, and you don’t want to be with me, fine. Get your ass dressed, little whore. That’s his name for me because he knows that the other daddy did the same thing to me. Not in the same way, I came out of that with bite marks, but it was still the same thing.

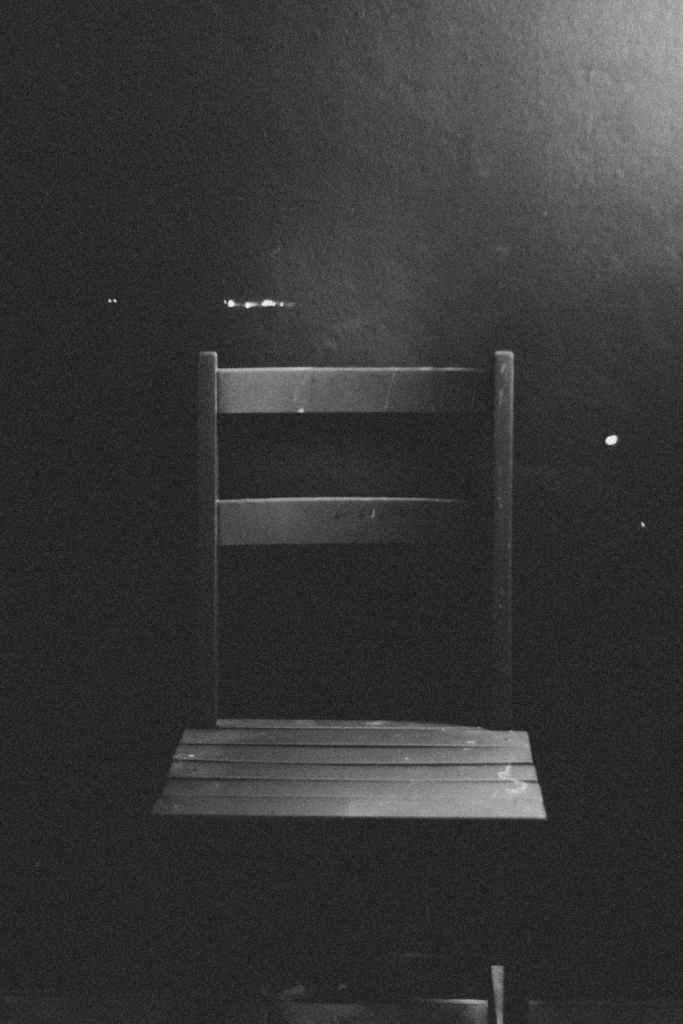

He lets me bring Apricot. He don’t always, sometimes I have to leave her in the big house, but he lets me bring her this time. As he drives, he talks about learning my lesson. He says nobody ever gets nothing for free. I stare at the room around me. He’s removed the mattress because, he says, I don’t want you to be comfortable. He also removed my pot for the bathroom. The only thing left is a simple chair. He probably left that here for him to sit in when he comes to see me. In a weird way, I’m happy to be back in The Radical Redress. It’s not got much, but I like that it’s quiet. It’s simple. Nothing can surprise me because I can see the whole room. Apricot wants to know what the best part of the house visit was. She likes stories, too. “I liked when Nan took us to the garden and let us plant those seeds.”

The gardens are huge.

Peach and apple trees are just the beginning. An arch covered in ivy and flowers leads into the most beautiful hideaway. Hedges of pink and white roses line one side of the garden while flowers of all the colors line cobblestone pathways. A second fountain, water spraying from the head of a lion, sits in the middle of the garden, and pretty white swings are tucked into alcoves beneath the swaying branches of tall oaks. My favorite part of the garden is the tamed wild: a small corner in the South end where wild honeysuckle and daises grow together: the stalks are taller and it’s not as clean-looking or tamed as the rest of the garden. For example, instead of one of the pretty swings, a simple, thick wooden plank, supported by a twisted yellow rope hangs from the branches of a weeping willow-swinging on that board is freedom. A cobblestone wall covered with moss, ivy and more flowers encloses the garden: it feels like it’s own little world. Nan took me and Apricot into the garden, gave us some seeds and helped us plant them.

“Remember how she said that the garden was now partly ours because we’d tended it?” Apricot stares back at me. I can tell by her smile that the memory makes her happy, too. I take a quivering breath, hug her close and close my eyes, hoping I’ll dream of the garden.

**** *** ****

Drip drip drip.

My fingers move to wash the water away before my eyes open. Confusion clouds my mind for a moment, making me frown. The Radical Redress is completely sealed. Nothing drips in here. I use my arm to push myself up off the cement floor and look around. It’s not until I look up that the breath gets stuck in my throat. There’s a hole in the ceiling and, from that hole, a spout. Black, rimmed, exactly the same size as the hole it’s poking through… and dripping water. Splat. Another drop lands on my forehead, making me shake my head vigorously. Without warning, I grab Apricot’s soft arm and scramble to the side of the room, away from under the dripping water.

Water.

I feel Apricot dangling from my fingers and bring her closer to my chest. She’s scared. “It’s okay. It’s just dripping. See, just a couple drips, real slow. He’ll come and turn it off, it’s okay.” I hug her, then sit against the wall. My eyes bounce from the water coming from the ceiling to the walls. There’s nothing here. Nothing at all. He took my pot. He took the mattress. Only the chair remains.

He sits in the chair, staring at me.

“Take the clothes off. Let me see what’s mine.”

I hate undressing in front of him. I don’t like being undressed at all but I really don’t like undressing when he’s watching. It hurts when he puts himself inside me. It hurts, and I feel like I’m ripping, and I know that taking my clothes off is the first part of that. He ain’t as bad as the other daddy, the one at the shack. That was worse. One time, my arm broke; I heard the bones snap. It never fixed all the way. He’s not like that. But just cause it ain’t as bad as my real daddy don’t mean it don’t hurt. When he’s done, when he stands up, I curl up, holding my arms around my waist, tears leaking from my eyes. “Dry it up, don’t act like you didn’t start that. You’re the one who took your clothes off. Hell, you touched me first. Looking at you, I’m the one who should be crying. Dry it up.”

I look at the water: it’s still dripping. On the floor, there’s a very small wet spot that’s slowly widening with every splat. My stomach rolls. I look down at Apricot and run a finger over her hair. It’s in pigtails. “Would you like to see what you look like with your hair down?” I ask. Gently, I pull the rubber bands out of her hair, feeling the fabric strips slide through my fingers. “I wish my hair was like yours, Apricot.” She smiles back at me, like always. I wish I was like her: always happy.

“I hope he comes soon,” I say, ignoring the water trickling down. “I’m getting a little hungry.”

Drip drip drip.

**** *** ****

When I fall to sleep, I’m falling, falling, falling through the rotten boards at the old shack into the soft dirt beneath the porch. Hundreds of bones start laughing, rattling as they rise to chase me as I crawl hopelessly through the dark space under the house. I’m lost and there is no escape. The dream makes me jerk awake, my fingers patting the floor to find Apricot. Wet splashes my fingers. I gasp, sitting up, fear clutching my throat. Apricot is still on my chest; she’s safe. I hug her close and look up. The trickle is now a steady stream: the floor is covered in a thin layer of water, enough that the backside of my clothes are drenched from laying on the floor. Swallowing, I scramble to my feet. Apricot looks at me, asking what are we going to do. I can tell she’s scared too. The only one who can help her is me.

“It’s okay,” I say. “We’ll use the chair until he comes.” I walk, my feet swirling the thin layer of water, and sit in the chair. The sound of the water spilling onto the floor is louder now, the sound of water slushing around my feet is loud.

Like the pond.

The water rises. As I watch it, panic starts to bubble in the back of my throat. Memories from the pond collide with questions about the water. There’s no where for it to go. I look around the room, already knowing there’s no way out. The water is rising. Apricot doesn’t know how to swim. The chair.. will the chair stay still? If I put my feet down, the water is about halfway to my knees. It is rising. Apricot can’t swim. I hold her close to me, up high, near my neck.

I’m little, six or seven, I can never remember how old I am. Nobody does. Daddy never tells me. He says birthdays are fake, that they were created for the businesses to make money, that they don’t mean nothing, and he can’t even remember when I was born. He’s asleep, so it’s a good time to get clean. The walk to the pond is not far. Mosquitoes fly near me; I swat them away. The path gets darker the farther I walk, sunlight blocked by trees standing close together. A low hum plays low along this path: it’s the sound of the critters who live here. By the time I get to the small clearing and see the pond, I am proud of myself. It’s the first time I’ve come to bathe alone. I can do big things.

I can’t get out.

The door is locked.

There’s no windows.

The water rises. It’s almost to the seat of the chair now.

Apricot can’t swim.

I stand up on the chair: it wobbles. Panic fills my lungs and I scream, unable to stay quiet. When is he coming? I hug Apricot, looking around the room. That’s when I see something I’ve not noticed before. There’s a new, small window in the door. He’s here! I see my new Daddy, Jonathan, standing outside the glass. I can only see his face and neck, but he’s here! Relief washes through me. He’ll unlock the door. I climb down off the chair, holding Apricot up high. The water is to my waist now but I can still stand. I trudge through the water to the door, waiting for it to open. It doesn’t. Instead, he smiles at me, holds both hands up to show me they are empty. No key.

My brain fails.

Fear turns wild. I use one hand to beat on the door, I twist and point at the water he clearly sees. Suddenly, I’m struck by a thought: he removed everything from the room. He drilled the hole in the ceiling, added the water spout, turned it on. He did this. He’s not opening the door. Fear pushes out any sense of pain. I have to get higher than the water; it’s almost to my breasts now. Apricot can’t swim. Wild terror streaks through me, flashes of the pond lash through my mind, one after the other. I start screaming.

I never see him.

Instead, I feel someone jerking me by the hair, I hear him yelling at me. Suddenly, without warning, hands push me under the water. The murky green waters close around my ears, clogging them, and fold over my face, my nose. I can’t see him, the water isn’t clear, but I can’t breathe. I kick my feet, flail my arms; I can’t turn my head because his palm is flat against my nose, his fingers curled into my temple. He’s holding me under the water. My lungs hurt, my foot kicks his arm, but he doesn’t move. I twist my body but nothing happens. Terror fills me. Everything’s starting to turn black; the edges of my vision — I hear the water rush, feel my body being yanked upwards. Air hits my face; I gasp for it, begging for it to fill my lungs. It is the last time I ever get in water.

I stand on the chair, holding Apricot, the water almost to my neck. I talk to her. She’s crying, she’s scared. I talk to her, tell her I can keep her safe, I’ll keep her dry. I have to get her somewhere higher. I hold her above my head. I scream again, look toward the door. Jonathan’s still there, watching. When I look at him, he stares. He’s not smiling now, he’s just watching. The water will kill me. The water will kill Apricot. My fingers clench around her fabric.

“Do you see that?” I ask Apricot, pointing. Beyond the pool, I can see the barn and the ring where the horses are ridden every day. There’s one in the ring now. They jump over a white bar, landing safely. Apricot wants to try. We walk into the room, near the desk’s chair. I move her up and down, like she’s riding a horse. “Faster!” she says, so I make her go faster through the air. “There’s the bar! Get ready!” I warn, bringing her closer to the chair. Suddenly, I push her higher into the air as she jumps the top of the chair. She giggles. The sound of cheering makes me look around: “look at the people, Apricot! They’re cheering for you!”

I scream as the chair tips over, swept out from under us. Water rushes up my nose and in my mouth as it closes over my head. I can feel his fingers holding my face beneath the water, I cannot breathe. My toes push against the floor; I can still stand on my tiptoes. My head pops up above the water. “Apricot!” I scream. When I fell into the water, my hands opened and she’s gone. Why did I let her go? How did I let her go? I can’t see her anywhere. I scream her name, my hands reaching under the water, splashing water everywhere as I try to grab a strip of her hair or a piece of her dress. The pink and white dress with the heart. I love you. I love you. Sage. Nothing.

Fear is panic. Suddenly, there’s less noise. I look up to the ceiling; the water is off, but I’m no less afraid. Apricot can’t breathe. She can’t swim. I can’t go under the water, I can’t, but I have to find her. I let her go. Why did I let her go? I scream for help, and look toward the door. Jonathan still stands on the other side, watching. I am crying, crying harder than I’ve ever cried. I have to find Apricot. “Look — the ceiling here is different than in The Radical Redress. Sage, look.” But he’s so heavy, and so big. When he hurts me—I squeeze my eyes shut and whimper. “Sage.” I hear Apricot calling me and I open my eyes again. I can’t hold her, but I can see her, laying on the dresser. “Look at the ceiling.” My eyes move from her to the roof. It’s bumpy white plaster. “Do you see the mountains? I see horses; they’re racing!” I don’t see horses or mountains. Jonathan jerks so hard my body scoots upward; I feel something rip. “Here they come!” Apricot says. I try to focus on the ceiling. Where are the horses? Wait… I can see them! Apricot giggles and her smile, the painted on black smile, seems a little wider.

“Apricot!”

The water seems to be going down. It’s not at my neck anymore, it’s almost back to my chest, I can stand flat footed on the floor now. But I don’t see Apricot. I spin around, splashing water, trying to see an arm or a piece of her dress. I don’t see her. A black hole forms in the pit of my stomach. When I did let go? I was holding her, I had her in my arms… didn’t I? My favorite story is of the ladybird. The ladybird was sent by the heavens to bring luck to those who spot it. You can only spot ones that are meant for you and, if you’re lucky, it’ll land on your hand. If one lands on you, make a wish! You can ask for as many wishes as it has black spots and, if it flies away without any help, your wishes will come true! I asked Apricot where to find the ladybirds and she said, the garden. We ran outside and sat in the Tamed Wild. Apricot, look! I felt so excited when a beautiful ladybird landed on my arm. It was bright red with seven black dots. I didn’t know seven things I wanted, so I only made five wishes. I think of the big dinner: they let me eat inside the big house and there was lots and lots of food. I wish he wouldn’t make me do the touch tonight. He didn’t. The other three haven’t come true yet. I’ll give those wishes back, ladybird, I don’t need them. Just let me find Apricot.

The water is almost gone; I can see the floor of the room again.

But I don’t see Apricot.

I’ll never see Apricot again.

I sob, my chest heaving, my heart beating heavy. I push my hand against my mouth, biting it to keep from screaming anymore. The water is draining through a hole in the corner of the room that I didn’t see before. I stare at that hole, watching as the last of the water gets sucked into it. Did Apricot get sucked into that hole? Is she stuck in that hole now? Suddenly, without warning, I hear click clack clack. I turn towards the door, my heart beating like a maddened thing again, fear leaping into my throat. Jonathan is gone, but I know what that sound was. I’ve heard it time and time again.

The door is unlocked.

[…] Beyond all that, though, I’m mostly proud of this story because it pushed me further. Apricot, the chapter, is based on a series of nightmares that I really do have. They are terrifying and […]

[…] Apricot […]

[…] Apricot […]